Client Alert

Top PHive Crypto Enforcement Notes: October Edition

October 03, 2022

By

Laurel Loomis Rimon,

Leo Tsao,Kenneth P. Herzinger,Michael L. Spafford,Braddock J. Stevensonand Ben Seelig

We knew there would be plenty to write about each month, and so we start with a mention of the White House’s Framework for Responsible Development of Digital Assets, issued on September 16, 2022. While the Framework itself doesn’t result in any immediate changes, it incorporates a number of reports from DOJ, Treasury, and other agencies that outline government assumptions and approaches that are reflected in the topics we discuss below. The administration repeatedly calls for “aggressive” enforcement by law enforcement and regulators. Of course, enforcement is easier and faster to put into action than, say, new guidance, legislation or regulations. We also keep an eye on the government’s views on DeFi, including on cryptosphere participants who may have thought they were outside of scrutiny, as well as calls to regulate NFTs and expand jurisdiction and penalties for crimes related to transmitting digital assets. At least the government’s fiscal year ended September 30th, so maybe there will be a brief break in the action . . .

- CFTC Moves Aggressively Against DeFi

- The SEC Widens its Cryptocurrency Net to Capture Secondary Actors and Service Provider Payments

- The OCC Flashes Warning Lights on Bank-Fintech Partnerships

- Beat the Day One Subpoena (or CID) Scramble

- Tornado Cash Part II: Licenses, Lawsuits, and Dusting

|

|||

- CFTC Moves Aggressively Against DeFi

What is the legal status of a decentralized finance platform – is it a legal entity (a corporation, partnership or association), a distributed ledger or a smart contract? And, who is legally responsible for its actions or misdeeds – the founders, the architects of the contracts, the holders of the governing tokens, the protocol that administers the smart contract, the smart contract or distributed ledger itself, the node operators, or no one? The CFTC recently weighed in on this debate in a speaking order approving the settlement of claims against bZeroX (a corporation that administered the bZx Protocol and bZx DAO) and its two founders, Tom Bean and Kyle Kistner (the “Order”). The CFTC also filed a federal district court action against Ooki DAO, the successor to the bZx DAO (the “Complaint”).

Analyzing the allegedly-illegal conduct first, all five Commissioners agreed that ETH, and virtual currencies based on the ERC20 token, are commodities under the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA). The Commission also unanimously determined that the bZx DAO, which controlled and operated the bZx Protocol, and its successor the Ooki DAO, solicited and executed illegal off-exchange retail transactions with U.S. customers involving “leveraged positions whose value was determined by the price difference between two digital assets.” Leveraged retail U.S. commodity transactions not delivered within 28 days must be transacted on or subject to the rules of a designated contract market. There is nothing particularly new or unusual about these charges, as the CFTC has consistently exercised enforcement authority over leveraged retail transactions occurring within the U.S. or involving U.S. residents.

What is new are the CFTC’s findings regarding the Ooki DAO and the individual founders. According to the Order, “the Ooki DAO meets the federal definition of an unincorporated association,” which it defines as “a voluntary group of persons, without charter, formed by mutual consent for the purpose of promoting a common objective.” The Commission focuses on the Ooki Token holders who, by virtue of owning Ooki Tokens, have the right to propose and vote on changes to the Ooki Protocol (previously the bZx Protocol) or otherwise shape the direction of the DAO’s business, including, for example, controlling the administrator keys used to access the smart contracts involved in the leveraged trading. Thus, the Complaint alleges that the “Ooki DAO is an unincorporated association comprised of Ooki Token holders who have voted those tokens to govern the Ooki Protocol.” (Emphasis added).

The CFTC found that the individual co-founders were controlling persons, and, therefore, liable for the actions of the corporation they owned, bZeroX, which operated the bZx Protocol and bZx DAO. The CFTC then went further and took the unusual step of leveraging state law to find the bZeroX co-founders personally liable for the actions of the independent Ooki DAO based solely on their participation as Ooki Token holders. Under state partnership law, the individual members of an unincorporated association organized for profit may be jointly and severally liable for the debts of the association. The Ooki DAO, the Commission concluded, is a for-profit, unincorporated association because it charges fees for its products and services, generates revenue that it distributes to its members, collects and liquidates collateral, and offers ownership rights in the DAO in the form of Ooki Tokens. Applying state joint and several liability partnership law, the Commission concluded that the founders were “personally liable for the Ooki DAO debts” because, as “members of the for-profit Ooki DAO unincorporated association,” they voted on governance matters.

This was a bridge too far for Commissioner Mersinger, who dissented from the Order because it “arbitrarily” defines an unincorporated association as those token holders who exercise their voting rights (as opposed to those who do not vote) and may have the chilling effect of discouraging voting participation (which could undermine proper governance and compliance). Although Commissioner Mersinger agreed that an association (like a DAO) is subject to the CEA -- and voted to authorize the CFTC lawsuit against the Ooki DAO -- she did not agree with the proposition that the personal liability of DAO members may be based “on a State-law doctrine that members of a for-profit unincorporated association are jointly and severally liable for the debts of that association.” A federal enforcement action seeking civil money penalties is not collecting debts and should be based on the CEA, not state law. In her view, “it did not have to be this way,” because the facts were sufficient to support liability under CEA Section 13(a). The founders aided and abetted the Ooki DAO’s violation when they set in motion the Ooki DAO’s CEA violations (by setting up the Ooki Protocol in the same illegal manner as the prior bZx Protocol) and they announced that the Ooki DOA was set up to avoid regulatory oversight.

It is interesting that the parties did not resolve all claims relating to the bZx and Ooki Protocols in one global settlement, resulting in a CFTC lawsuit against the Ooki DAO. It appears that either the CFTC or the Ooki DAO is looking to make a point about the liability of DAOs (or other unincorporated associations), and, thus, wants a court to weigh in on the issues. The Ooki DAO lawsuit could help to define the scope of CFTC authority and provide clarity on the legal status of decentralized entities like the Ooki DAO, but, as Commissioner Mersinger points out, the Commission need not wait that long. It could engage now in rulemaking seeking public comments addressing “the novel and difficult public policy issues raised” by DAOs, rather than “regulating by enforcement.”

This is the second CFTC enforcement action against a decentralized finance platform this year, the first being its January 2022 order settling charges with Blockratize, Inc., d/b/a Polymarket.com, for marketing and transacting in illegal binary options. In both enforcement actions, the CFTC focused on the illegal conduct and not the structure or form of the entity engaging in that conduct. This is in keeping with a broader all-government focus on decentralized finance platforms, which looks past the platform (and its apparent decentralized nature) to the underlying conduct and seeks to hold all parties (including individuals) involved in the conduct accountable -- even if, as here, it has to find new ways to do it. (Contact: Michael Spafford)

- The SEC Widens its Cryptocurrency Net to Capture Secondary Actors and Service Provider Payments

We have all been hearing about the SEC’s cryptocurrency enforcement initiative for some time, but the SEC’s recent charges against Dragonchain are noteworthy because it’s the first time the SEC has charged affiliated companies for selling unregistered securities, and because the SEC’s charges sweep ordinary cryptocurrency payments to service providers into its enforcement net.

Dragonchain, Inc., a Washington corporation, allegedly had an initial presale with initial purchasers receiving 10%-30% discount, and later conducted an ICO. Together, these sales raised $14 million from approximately 5,000 investors.

On August 16, 2022, the SEC filed a complaint against Dragonchain Inc., Dragonchain Foundation, The Dragon Company, and Dragonchain’s founder in the Western District of Washington, alleging that the 2017 sale of DRGN tokens was an unregistered crypto asset securities offering in violation of Section 5 of the Securities Act of 1933. Notably, the Washington Department of Financial Institutions had previously entered into a consent decree with Dragonchain in January 2021, finding that its tokens were securities.

The SEC alleged the fortunes of DRGN purchasers were tied to one another and dependent on the success of Dragonchain’s strategy because the funds from the token sale were used to fund Dragonchain’s operations, and Dragonchain retained 45% of the DRGN tokens. At the time of the token sale, DRGN tokens were allegedly not available for consumptive use or as a medium of exchange, so the token purchasers allegedly had an expectation of profit.

The SEC alleged that Dragonchain did not direct its marketing of DRGNs to businesses who were interested in using its turnkey platform, but rather to the larger crypto community, and that Dragonchain paid sales-based commissions to crypto influencers who promoted its token. The SEC also alleged that Dragonchain’s marketing statements that the value of the DRGNs was expected to increase as the ecosystem matured, and its plans for DRGNs to be listed on secondary-token trading platforms, show that the token is a security. The SEC further alleged Dragonchain capped the number of DRGN tokens that would be created, assured investors that it would take steps to protect the market for DRGNs, and undertook efforts to promote DRGNs.

All of that is fairly standard regarding the SEC’s ICO enforcement cases. However, the SEC also charged as defendants two affiliated companies, the Dragonchain Foundation, a non-profit entity organized in Washington that owns the intellectual property associated with the Dragonchain technology and which received a portion of the proceeds from the 2017 presale and ICO, and The Dragon Company, a Washington corporation that provides adoption services for Dragonchain technology and the Dragonchain ecosystem, alleging that they participated in Dragonchain, Inc.’s illegal sale of unregistered securities. In addition, the SEC alleged that Dragonchain’s and the Foundation’s $2.5 million of token payments through The Dragon Company to contractors and service providers between 2019 and 2022 was part of a distribution with the view to sell the tokens on the open market and therefore constituted illegal sales of unregistered securities. The case also shows that no case is too old for the SEC because the alleged ICO sales and presales were in 2017.

For its part, Dragonchain responded with an open letter to the SEC. Dragonchain complained that, on April 27, 2022 in the final hours before the statute of limitations was to expire, the SEC Staff sent a letter to the defendants notifying them that they would recommend charges for the sale of unregistered securities in 2017. Yet, Dragonchain claims it had been communicating with the SEC for over four years, providing numerous answers and copious amounts of data, and was never given the opportunity within the regulatory process to offer a full explanation of its technology. The company asserts it has a very strong case against the SEC’s charges. The case is ongoing and the defendants have not yet answered or otherwise responded to the SEC’s complaint.

Whether the SEC can actually prove up its claims in federal district court is yet to be determined. In the meantime, however, blockchain companies, their affiliates and related decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), should take note that the SEC may investigate and pursue charges against them for sales of crypto assets in the open market and cryptocurrency payments to service providers. (Contact: Ken Herzinger)

- The OCC Flashes Warning Lights on Bank-Fintech Partnerships

On September 7, to kick-start another busy month in Fintech news, the Acting Comptroller of the Currency Michael J. Hsu outlined the OCC’s serious concerns related to the proliferation of bank-Fintech partnerships. In public remarks, Comptroller Hsu stated that the “de-integration” of banking services—meaning the outsourcing of new banking interfaces, products, and services to Fintechs—“if left to its own devices, is likely to accelerate and expand until there is a severe problem or even a crisis.” Hsu had OCC staff analyze supervisory data and publicly-available information to identify specific banks with multiple banking-as-a-service (BaaS) partners, and found numerous banks, mostly smaller banks, in this category. Hsu did not mince words in raising questions about whether these partnerships could lead to a race to the bottom with pressure to cut compliance corners and monetize user data.

To address these concerns and other “unknowns” about bank-Fintech arrangements, the OCC is executing a five-year strategic plan to enhance staffing and technical knowledge aimed at addressing the risks of banking digitalization and third-party dependencies. In plain English, enhanced supervision and enforcement of Fintech partnerships is coming and regulators will use data analytics to fuel it.

In particular, banking regulators are using advanced analytics to enhance bank supervision and create a regulatory data footprint of their institutions. The FDIC has launched FDITECH and Rapid Phased Prototyping, which are the FDIC’s tech lab and competitive process for developing technological tools for financial institutions. Since 2019, the Federal Reserve has relied on data-driven, forward-looking surveillance metrics through its Bank Exams Tailored to Risk (BETR) process.

As the FDIC says, “data is the new capital.” We expect these regulatory inititatives to be focused on bank-Fintech partnerships going forward. For example, banking regulators can analyze increases in non-interest income reporting from Call Reports to identify banks that may be entering or growing Fintech partnerships. Even a cursory review of historic bank enforcement actions highlights the theme of “growth outpacing compliance.” Comparing the increases in non-interest income that are the hallmark of new non-depository products with a bank’s SAR filings (part of the performance of which could be outsourced to a Fintech) or consumer complaint trends could provide a surveillance metric for regulators to develop enforcement targets.

Comptroller Hsu’s statements are a clear shot across the bow of banks and Fintechs. Banks with Fintech partnerships should be prepared for coming increased scrutiny, including by monitoring compliance services outsourced to their partners and understanding their regulatory data footprint. Fintechs should also be prepared for greater scrutiny as regulators leverage the Bank Services Company Act to examine their performance of bank functions. If deficiencies exist, Fintechs are at risk of losing their bank partnership or being subject to enforcement action themselves.

Banks and Fintechs should be conducting ongoing monitoring of key performance indicators in the areas of AML, consumer protection, cybersecurity, data security and sanctions screening to mitigate regulatory risk and maintain strong partnerships. They should develop mechanisms to quickly address deficiencies in these areas. And, banks and Fintechs should look at changes in the data reported to the government over time to assess the risk of triggering surveillance metrics. Being prepared to address these areas during an examination could be the difference between needing to address an exam finding and having to pay a Civil Money Penalty. (Contacts: Braddock Stevenson and Laurel Loomis Rimon)

- Beat the Day One Subpoena (or CID) Scramble

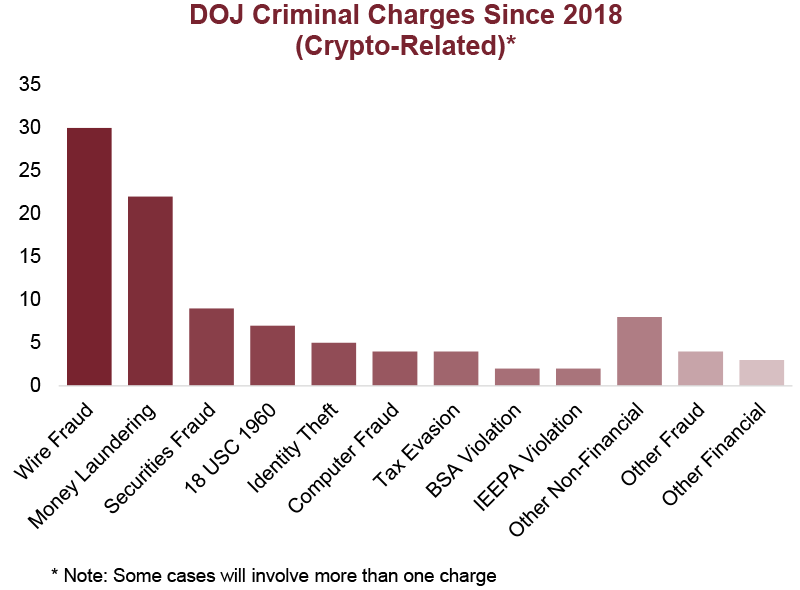

“U.S. regulatory and law enforcement agencies should, as appropriate, vigilantly monitor the crypto-asset sector for unlawful activity, aggressively pursue investigations, and continue to bring civil and criminal actions to enforce applicable laws with a particular focus on consumer, investor, and market protection.” – Treasury Department, Crypto-Assets: Implications for consumers, Investors, and Businesses, September 2022

In its Digital Assets Framework and related reports released in September, the Administration explicitly-directed federal regulators and law enforcement agencies to “aggressively” investigate the crypto-asset sector. With this in mind, it is worth spending some time thinking about how to be prepared for if (when) a subpoena, summons, or civil investigative demand arrives. To some extent, this is predictable. It’s not too much of a stretch to say that every financial services company—at least any of material size or operations—will face this eventuality. And, if the company itself, as opposed to one or more of its customers, is under scrutiny, there are certain documents and information that will almost certainly need to be produced in the initial stages.

Before discussing the likely nature of the demands the government will make, we note first that they will typically come with substantial time pressure. Somewhat counterintuitively, there is often more flexibility in response time for criminal grand jury subpoenas that come from DOJ or a U.S. Attorney’s Office, than for civil investigative demands that may come from the CFPB, FTC, or a State AG’s office. Regulatory agencies’ CIDs are typically issued pursuant to a regulations with strict and often inflexible time limits. Although extensions can be obtained, they may require detailed negotiations and will certainly still provide less time than a company would like.

There is always a scramble when a government information request comes in, particularly, if the company’s products, services, or operations are under investigation. Even the most well- established financial services company finds that its records are not in ideal order when it has to produce them. Often, Fintech and crypto companies have never faced this process, and have a steep learning curve in making a first production. However, the initial stages of responding to, and communicating with, a law enforcement or regulatory agency can go a long way towards influencing the trajectory of the investigation in a positive (or negative) way.

So, what to do to prepare? Have an organizational chart and key process flows. Especially, in a developing company, these things can be constantly changing. But the government gets skeptical when a company can’t produce a single such chart, immediately. Have an up-to-date description of the financial products and services being offered. That’s one of the first things that the government may ask for, and it often requires rounds of review by internal stakeholders to get one that’s ready for prime time. Identify the core policies and procedures that you would be uncomfortable admitting you do not yet have—this includes all procedures required by regulation (AML, for example), sanctions compliance, complaint handling, recordkeeping and retention, anti-fraud, cyber and data security, for example—and make sure to have at least an approved first-generation policy. Know where your data and records are held and stored (are they in the possession of a third-party vendor, for example), and what the retention period is. DOJ has just emphasized the importance of recordkeeping in its evaluation of corporate compliance, so this is a big one.

In short, a subpoena or CID for corporate records can be a substantial burden and long-term project. One way to attempt to shortcut the government’s investigation and increase the odds of a successful resolution to the investigation is to demonstrate quick and strong responses in the first instance to the requests that almost always come first. Consider this your ounce of prevention. (Contact: Laurel Loomis Rimon)

- Tornado Cash Part II: Licenses, Lawsuits, and Dusting

OFAC’s Tornado Cash enforcement action continues to make waves in the crypto community and beyond. As we explained in last month’s Top PHive, dozens of wallet addresses linked to the Tornado Cash protocol were sanctioned by OFAC in early August for the mixer’s alleged role in laundering funds associated with North Korea -- the first time the agency has added open source protocols to the SDN list. A lot has happened since then.

Following OFAC’s announcement, there were reports of celebrities and crypto personalities being “dusted,” or receiving unsolicited payments to their crypto wallets through Tornado Cash. Then, in early September, a lawsuit was filed in federal district court in Waco, Texas, by several users of Tornado Cash, claiming that OFAC’s sanctions designation violated the Administrative Procedure Act, as well as the First and Fifth Amendments. The complaint focuses on OFAC’s authority to designate software as a sanctioned person under E.O. 13694 and related regulations, specifically alleging that: “Tornado Cash is not a person, entity, or organization … [and] the software, including the smart contracts, consists of immutable open-source software code, which is not property, a foreign country or a national thereof, or a person of any kind.”

Indeed, the lawsuit wasn’t totally out of the blue. Many in the crypto and digital privacy spaces, and even a member of Congress, had been critical of OFAC’s move. In a letter from Rep. Tom Emmer to Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, the congressman argued that the mixer’s open-source software was no longer controlled by Tornado Cash’s founders or software developers, and asked for clarification on several aspects of OFAC’s action.

One of the points raised in Rep. Emmer’s letter was whether people with funds trapped in Tornado Cash’s smart contract would be able to reclaim their virtual currency. Treasury has subsequently clarified this point in FAQ guidance on the availability of specific licenses for U.S. persons wishing to complete transactions with Tornado Cash. Treasury also noted that, even though “dusting” was technically contrary to OFAC’s regulations, it would not prioritize enforcement involving these transactions provided that they “have no other sanctions nexus besides Tornado Cash.”

So, what does this all mean for compliance programs going forward? Even though Treasury’s new guidance provides a path for some individuals to withdraw funds that would otherwise have been considered blocked property, companies must still be diligent to avoid sanctions liability through transactions with the listed wallet addresses or with other wallets connected to the designated wallets.

The harder questions relate to historic transactions. While transactions involving Tornado Cash that pre-dated the sanctions designation are likely not required to be reported to OFAC, companies should consider a reasonable lookback review to identify exposure to past transactions involving the protocol, as it may be prudent to consider the filing of Suspicious Activity Reports. Our view is certainly that, pursuant to FinCEN’s regulations, the determination of whether to file a SAR should be based on information known at the time of the transaction—not later acquired information—we are aware of regulators holding different expectations when it comes to crypto, so these can be complicated calls.

Despite the outcry from the cryptosphere, mixers, and others, anonymity-enhancing virtual asset systems and tools are certainly still in the sights of regulators. The sharp decline in transactions using the Tornado Cash protocol since OFAC’s sanctions announcement is likely considered by the government to be a sign of success. Regardless of the civil challenge to OFAC’s sanctions designation and how that may pan out, many have already started to predict that the application of criminal and administrative obligations to software or smart contracts may eventually implicate other participants, such as miners and node validators, conducting proof of stake functions on the newly-merged Ethereum blockchain. (Contacts: Ben Seelig, Braddock Stevenson and Laurel Loomis Rimon)

- California’s Crypto Regulatory Flash in the Pan

Earlier this year, Assemblyman Tim Grayson (D-Vallejo) sponsored Assembly Bill 2269—California’s proposed Digital Financial Assets Law—designed to create a licensing regime that would cover “digital financial asset business activity.” The law would have gone into effect on January 1, 2025, and defined “digital financial asset” as a digital representation of value that is used as a medium of exchange, unit of account, or store of value, and that is not legal tender.

Similar to New York’s Bitlicense, California’s law would have covered a broad range of activities, including issuance of digital assets, exchange, transfer, custody, as well as issuing certificates related to interests in electronic precious metals and exchanging digital representations of value within online games, among other things. The proposal did not include reciprocity for licenses issued by other states, although entities such as banks, credit unions, some payment processors, foreign exchange businesses, software and data security providers, and those engaged in personal or household use would have been exempt. The legislation did require evaluation of potential securities laws issues, and proposed criteria for the handling and backing of stablecoins. Licensees would be subject to examination, and operating without a license in California could result in sanctions.

This was not the first attempt by California to create a regulatory regime applicable to crypto, but it was the most detailed, and the one that came the closest to being enacted. Strong opposition from the industry created headwinds, with claims that the proposed legislation was overly restrictive, creating barriers to innovation and placing undue expense on crypto businesses already operating in California that would have to come into compliance with the new requirements.

In the end, on Friday September 23, 2022, California Governor Newsom vetoed the legislation, stating that “[i]t is premature to lock a licensing structure in statute” without fully taking into account the research his administration has been doing, as well as “forthcoming federal actions,” by which he presumably means potential federal legislation of the kind that has been recently proposed regarding stablecoins in particular. Governor Newsom’s action may also recognize the challenges of coordinating a Digital Asset licensing law with an existing money transmission regime—a challenge present in New York, for example—and reflect a genuine effort to proceed cautiously.

Thus, California remains in the in-between. It’s possible to do crypto business there without a license, but beware the Department of Financial Protection and Innovation is increasingly stepping into the void, collecting consumer complaints, providing alerts to the public, and cataloguing enforcement wins. (Contact: Laurel Loomis Rimon)

To receive regular updates, please click here to subscribe to Top PHive Crypto Enforcement Notes.