Client Alert

Top PHive Crypto Enforcement Notes: September Edition

September 07, 2022

Laurel Loomis Rimon, Leo Tsao, Braddock Stevenson, & Ben Seelig

Greetings, and thank you for taking a look at our new monthly crypto enforcement newsletter. Our goal is to share five topics each month that we believe are of significance in the world of crypto enforcement—particularly as they relate to anti-money laundering, sanctions, and consumer protection, although we’ll touch on other topics where they intersect. We aim to provide a quick recap of significant events, along with our thoughts on why they matter, as informed by our work in the trenches advising clients and interacting with federal and state regulators. We hope you’ll finish reading this saying “hmm, I hadn’t thought of that” at least once, and maybe with an item or two to add to your compliance task list. You can thank us later . . .

- Chief Compliance Officer Certifications: Should Compliance Officers Be Worried?

- Tornado Cash: OFAC’s Twister-Mixer Enforcement Action

- Virtual Currency SARs on the Rise

- What’s in a Certification?

- Four Month Anniversary of NY DFS’s Blockchain Analytics Guidance

1. Chief Compliance Officer Certifications: Should Compliance Officers Be Worried?

Kenneth Polite, the Assistant Attorney General in charge of the DOJ’s Criminal Division, has marked his tenure by prioritizing the empowerment of Chief Compliance Officers and their departments. As a former CCO himself, AAG Polite has emphasized that compliance departments play an outsized role in detecting and preventing corporate misconduct. On March 25, 2022, AAG Polite floated an idea that the DOJ may use a new tool to “further empower” compliance departments by requiring the CCO and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of a company that has entered into a resolution with the DOJ to sign a certification about the design and effectiveness of the company’s compliance program.

The AAG’s proposal was put into practice in May 2022, when the Criminal Division imposed this certification requirement for the first time as part of a corporate resolution. Specifically, in a new Attachment H to the agreement, the DOJ required the company’s CCO and CEO to sign a certification at the end of the Agreement’s term affirming that: (1) they “are aware of the Company’s compliance obligations under . . . the Agreement;” (2) based upon their “review and understanding of the Company’s . . . compliance program, the Company has implemented . . . [a] compliance program that meets the requirements” set forth in the Agreement; and (3) the “compliance program is reasonably designed to detect and prevent violations [of applicable laws] throughout the Company’s operations.” To add teeth to the certification, it also included acknowledgments of the possibility of criminal prosecution. Recent statements by the Criminal Division’s Fraud Section indicate that such certifications will be included in all future corporate resolutions.

CCOs may understandably be concerned about the threat of prosecution if the company’s compliance program is later found to be deficient under the DOJ’s criteria, and corporate misconduct results in individual liability. That is especially true given that the DOJ’s standard uses amorphous terms such as “reasonably designed.”

As a practical matter, however, it does not appear that CCOs presently have much reason to be concerned. First, the reach of the new requirement is narrow because it only applies to companies that enter into corporate resolutions with the DOJ. Thus, this requirement is unlike the certifications required of CEOs and Chief Financial Officers under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which apply to all public companies. Second, the process used by the DOJ and companies to reach a negotiated resolution typically involves detailed discussions about the current state of the company’s compliance program and the company’s plan for remediating any deficiencies. Moreover, during the pendency of the term of the Agreement, the DOJ will receive reports about the company’s progress (either through a monitor or the company’s own self-reporting) and will communicate its concerns to the company. Thus, in most cases, the expectations for meeting the DOJ’s requirements should not come as a surprise. Finally, prosecutors will likely exercise their discretion to prosecute CCOs in only the most egregious cases. As one Criminal Division supervisor recently explained, the certification is not intended to “provide fodder” to prosecute CCOs for good faith misstatements. He added, however, that “if someone affirmatively lies to us” and the misstatement “is made knowingly, then they may be prosecuted for a false statement.”

Nonetheless, this development reflects a growing focus on ensuring that compliance personnel are properly placed in a company’s hierarchy, sufficiently empowered and resourced, and fully exercise their authority. Not only will the DOJ take this into account, but regulatory supervisors are also highly focused on this issue.

2. Tornado Cash: OFAC’s Twister-Mixer Enforcement Action

Nearly a month ago, OFAC announced a first-of-its-kind sanctions designation of a decentralized platform, and the move continues to reverberate throughout the crypto ecosystem. There’s little question that the allegations against the smart-contract mixer Tornado Cash are serious: namely that the platform was used to launder $7 billion worth of virtual currency, including money stolen by the Lazarus Group, and funds from the Harmony Bridge, Ronin Bridge, and Nomad Bridge heists. But what does OFAC’s Tornado Cash action mean for enforcement (and compliance) writ large?

One thing is clear: mixers and other anonymity-enhancing virtual asset systems and tools are squarely in the scopes of regulators. Tornado Cash joins the ranks of Blender.io which was sanctioned by Treasury in May 2022, and Helix and Coin Ninja which were hit with penalties by FinCEN in 2020, though FinCEN only has a month left to actually collect those penalties. As a recent Chainalysis report on mixers found, “25% of mixed funds come from illicit addresses, and cybercriminals associated with hostile governments are among those taking the most advantage.”

The move by OFAC also indicates that the agency doesn’t distinguish between centralized or decentralized applications. In other words, the Tornado Cash action strongly suggests that decentralized systems may be held to at least some of the same compliance obligations as centralized systems or products, and that regulators won’t refrain from taking enforcement action against smart-contract based platforms that are ostensibly operating without any “persons” behind them. Of course, human beings write the code that powers protocols, and the arrest by Dutch authorities of a man suspected of developing Tornado Cash is a sign that regulators will go after those folks as well.

Even though E.O. 13694 limits sanctions to “persons” (which are defined to include a partnership, association, trust, joint venture, corporation, group, subgroup, or other organization), it’s possible that this is the first government action that defines a decentralized application as an entity. The impact of such applications being considered “entities” by the U.S. government opens up significant liability across multiple criminal and administrative obligations.

A few questions remain. Is the government taking the position that decentralized platforms are nonetheless “persons” as that term has been broadly defined in prior Executive Orders establishing sanction authority? If source code is generally considered constitutionally protected speech under Bernstein v. Department of Justice and related precedents, do bans on creating or interacting with certain kinds of open source code implicate first amendment concerns, or constitute “prior restraint” on constitutionally protected speech? And, on a practical level, if enforcement on open source crypto platforms proliferates, how will regulators enforce strict liability prohibitions on U.S. persons engaging with the targeted technology? Finally, for current day compliance, OFAC’s designation of Tornado Cash provides a good opportunity to review the quality control on your screening systems.

3. Virtual Currency SARs on the Rise

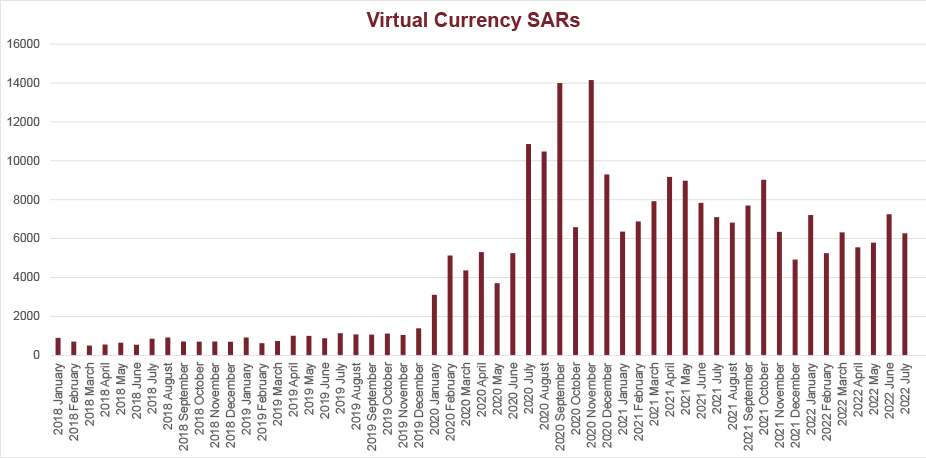

FinCEN’s SAR Stats suggest that the number of annual virtual currency SARs has increased exponentially over the past five years. While FinCEN and other federal regulators have stated for years that the number of SARs an institution files is not necessarily indicative of their anti-money laundering compliance, few, if any, financial institutions strive to be at the bottom of the SAR filing list. However, without specifics from FinCEN it is difficult for virtual currency exchanges to determine how their SAR numbers measure up. FinCEN has not added a “virtual currency” box to the SAR XML Schematic and virtual currency exchanges are lumped in with other financial institutions like money transmitters or banks (for state chartered trusts).

Despite the lack of specific drop-downs in the SAR form itself, virtual currency exchanges can get a sense of the filing numbers of the industry as a whole through FinCEN’s SAR stats page. Historical statements by prior FinCEN Directors suggest MSB SAR filings indicating “other” as the monetary instrument type correlate substantially to virtual currency SARs filed by money services businesses. (Note: In conducting this analysis, one needs to remove the Product Types that are specifically not virtual currency). For example, in November 2019, FinCEN Director Kenneth Blanco highlighted that FinCEN had received approximately 6,600 SARs from virtual currency exchanges since FinCEN’s May 2019 guidance. A SAR stats review of MSB SAR filings with “other” as the monetary instrument type and no specified product type or “other” specified product type shows approximately 6,300 SARs filed during that time period. Additionally, statements in FinCEN Director Blanco’s August 2018 speech indicating that FinCEN was receiving over 1,500 SARs per month related to virtual currency could be matched to other FinCEN statements that half of such filings are made by virtual currency exchangers, and a review of the SAR stats numbers showing that such SAR filings were between 600–800 per month in the months leading up to August 2018. This is fuzzy math, but does provide some insight into industry trends.

As the graphic above shows, the number of monthly SARs filed by MSBs involving an “other” monetary instrument has increased significantly in the past two years. Within these increases, there are spikes of filings that occurred one month after the issuance of advisories significant to the virtual currency industry. There were approximately 14,000 SARs filed in September 2020, a month after FinCEN issued its advisory on cybercrime on July 30, 2020. And, again in November 2020, SARs rose to 14,000 in the month after FinCEN issued its advisory concerning red flags for ransomware activity on October 1, 2020.

It is clear that FinCEN is monitoring the numbers of SARs filed in the virtual currency industry and has noticed the significant increases since 2018. Virtual currency exchanges should take note of these increases and review how their numbers compare to these recent trends. Exchanges whose numbers have remained stagnant may face increased scrutiny and should have documented reasons justifying the reasonableness of their SAR filings. Additionally, SAR filings are not only an opportunity to report suspicious activity but also educate the regulator on trends in the industry. Narratives that demonstrate a more nuanced approach beyond reciting a blockchain analytics hit could help nudge FinCEN and state regulators towards a better understanding of suspicious activity in the cryptocurrency world.

4. What’s in a Certification?

There are two required annual certifications that blockchain based financial institutions doing business under New York’s Bitlicense regime must complete and submit each year by April 15. Under Parts 200 and 500 of New York’s Codes, Rules, and Regulations, companies must separately attest that their cybersecurity and transaction monitoring programs meet New York’s requirements. In both cases, New York’s regulation is more specific and expansive than related federal requirements. NY DFS describes the certifications as a “critical governance pillar” and specifies that certifications may only be submitted if an entity is in compliance with every element of the multi-pronged requirements. A missing, inaccurate, or unsupported certification can itself be the basis for an enforcement action. And the fact that the certifications must be authorized by a company’s Board of Directors or Senior Officer only raises the stakes. The former regulators and prosecutors among us think “boy, this certification requirement sure makes for a tidy enforcement referral package.”

In real life, the certification requirements are sobering. Most crypto-native companies are building compliance programs from scratch under challenging and fast-moving circumstances. Incomplete or deficient certifications from earlier years may come back to haunt a company that is facing negative findings in a later-in-time examination. Although NY DFS cares about every element of its regulatory requirements, certain pieces seem to draw particular focus in certification discussions. Namely, having qualified people in both the CCO and CISO roles, with the appropriate authority and reporting lanes. Transaction monitoring resources are calibrated to the size, risk, and nature of transactions, and subject to internal audit and revision on an ongoing basis. Strong data management and integration is used in transaction monitoring. As to cybersecurity, updated risk assessments, sufficient and properly qualified staff, and written Business Continuity, Disaster Recovery, and Incident Response plans are key.

The lesson here is, even though the certification occurs retrospectively, don’t let it be an afterthought. It takes significant advance planning to be in a position on April 15 to properly certify compliance for the prior year. Let the certification be your guide before the year even starts.

5. Four Month Anniversary of NY DFS’s Blockchain Analytics Guidance

Okay, maybe four months is not a true milestone, but this past April, the New York Department of Financial Services issued specific guidance to virtual currency businesses that operate in New York outlining expectations related to the use of blockchain analytics. This was noteworthy at the time—not just for New York businesses—and is worth revisiting now that it has settled in a little bit. The question of what a successful AML program looks like for a blockchain based financial institution is still open, and requirements for transaction monitoring are a key part of that question. With this guidance, NY DFS attempts to answer the question. Given New York’s Part 504 requirement that businesses annually certify their transaction monitoring compliance, its guidance carries particular weight. Although the guidance does not apply to virtual currency companies not doing business in New York, in our experience, NY DFS is saying what other regulators are also thinking (and in some cases have directly expressed to us) when it comes to expectations about the use of blockchain analytics.

At a high level, NY DFS’s blockchain analytics guidance puts in black and white that blockchain based financial institutions must broadly utilize blockchain analytics services, whether their own proprietary solutions or those of outside vendors. No surprise there. DFS also comes right out and says that the expectations for monitoring the activities of customers are different than with fiat, due to the nature of blockchain transactions and the availability of provenance and attribution information. So, a “traditional” transaction monitoring approach cannot be simply transplanted into the cryptocurrency environment. And, importantly, written policies, procedures, and operating guides need to explicitly integrate with blockchain analytics services, which requires a level of specificity around analytics services and how they are managed by compliance staff that might not be intuitive.

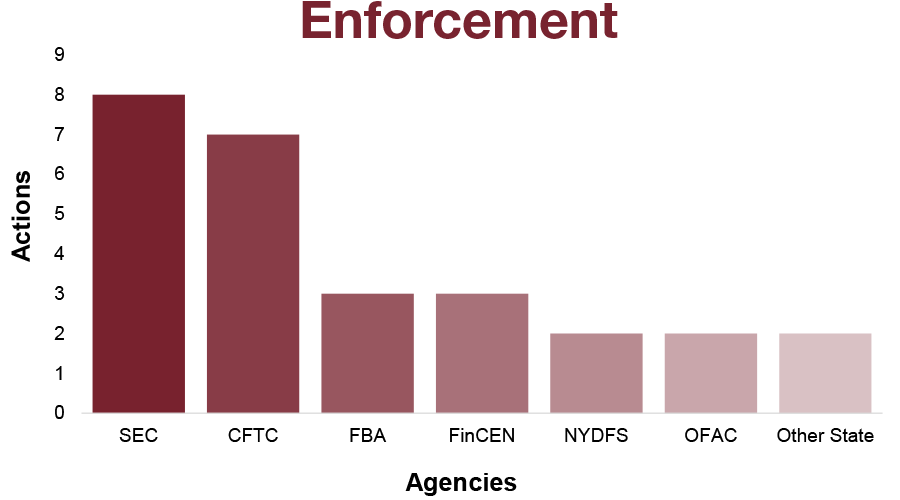

When it comes to enforcement, regulators on the state and federal level are themselves relying to a large extent on blockchain analytics services. While they have developed some internal capabilities of their own, they also use the very same analytics resources available to the private sector. When it comes to supervisory findings or even enforcement actions, regulators are often inclined to consider their work done if they’ve identified a “suspicious” transaction using the rules and practices they have established for themselves. Yet, there is more to do here, both in educating regulators about when and how a blockchain alert truly requires the filing of a SAR, and establishing reasonable best practices that will survive the scrutiny of law enforcement. It’s not always as simple as filing a SAR for every alert of your blockchain analytics vendor.

Contributors