Client Alert

Top PHive Crypto Enforcement Notes: January Edition

January 13, 2023

By

Laurel Loomis Rimon,

Leo Tsao,Kenneth P. Herzinger,Michael L. Spafford,Braddock J. Stevensonand Ben Seelig

Click here to subscribe and receive the Top PHive Crypto Enforcement Notes in your inbox.

Click here to subscribe and receive the Top PHive Crypto Enforcement Notes in your inbox.

Happy New Year! While the holidays hopefully provided a chance to rest and recharge, things have not slowed down in the world of digital asset enforcement. We see a growing dedication of resources by government law enforcement agencies and financial regulators related to the oversight of cryptocurrency, and a sense that government agencies are moving faster to intervene and take action. As always, we hope our take on some of the events of the last month provide useful guidance as we go forward this year.

- Wire Fraud Remains The Go-To Tool for Federal Prosecutors in Cryptocurrency Cases

- SEC tells public companies to disclose crypto exposure: So now what?

- How to Serve a DAO: An Ooki DAO Update

- Federal Regulators Flash Red Lights at Banks’ Involvement in Crypto

- FinCEN will Grant Limited Access to Beneficial Ownership Information for Financial Institutions

- Wire Fraud Remains The Go-To Tool for Federal Prosecutors in Cryptocurrency Cases

The wire fraud statute is undoubtedly expansive. As a general matter, wire fraud can be used to charge any defendant who has “devised, or intended to devise, a scheme or artifice to defraud” that is executed using an interstate or foreign wire. 18 U.S.C. § 1343. Given its broad scope, wire fraud has been used to charge a wide range of crimes including both traditional fraud schemes (such as securities fraud or Ponzi schemes), as well as less obvious crimes (such as bribery, immigration offenses, and economic sanctions violations). In addition to being an extremely versatile tool, however, wire fraud can also be a very powerful tool because it is often simpler to prove, has broad extraterritorial application, and offers many options for venue. As Judge Jed Rakoff once stated, it is for these reasons that federal prosecutors consider the mail and wire fraud statutes as “our Stradivarius, our Colt 45, our Louisville Slugger, our Cuisinart — and our true love.”

With respect to cases involving cryptocurrency and other digital assets, wire fraud is a particularly attractive charging tool. The advantages of wire fraud have been confirmed by

the recent wave of charges brought by the Department of Justice in such cases.

First, a wire fraud theory will often be simpler for prosecutors to prove. One of the most difficult legal issues with respect to digital assets is whether they qualify as a “security” subject to the securities laws. Indeed, the Securities and Exchange Commission has recently brought a number of enforcement actions involving digital assets, and in each case, the SEC will be required to prove that the relevant digital assets are securities under the so-called Howey test. In parallel criminal actions brought by the DOJ, however, the DOJ proceeded by charging wire fraud either instead or in addition to securities law violations. While the DOJ will still be required to prove a scheme to defraud, a wire fraud charge does not require prosecutors to prove that securities were involved, thereby avoiding this difficult legal issue altogether and allowing the DOJ to move more expeditiously.

Second, wire fraud can be used to address crimes occurring substantially overseas. Courts have repeatedly found that the wire fraud statute can reach extraterritorial conduct so long as the scheme is executed using the U.S. wires. For cases involving digital assets, where both the defendants and their misconduct can be based outside of the United States, wire fraud thus can be an attractive charge. One recent case, United States v. Elbaz, 39 F.4th 214 (4th Cir. 2022), underscores the wide extraterritorial reach of the wire fraud statute. In Elbaz, the defendant was convicted of wire fraud charges for carrying out a multi-million dollar investment fraud scheme that she devised and conducted entirely from Israel. As part of the scheme, however, the defendant made a phone call and sent emails (which qualified as wires) to three victims located in Maryland. The court of appeals affirmed the conviction, holding that the use of the U.S. wires rendered the application of the wire fraud statute permissibly domestic.

Third, wire fraud provides prosecutors with greater choices with respect to where they can bring criminal charges. For wire fraud, venue lies wherever the wire fraud scheme “occurred,” including where each wire transmission was sent and where it was ultimately received. Thus, a U.S. Attorney’s Office could bring charges in their district even if the only connection was that a wire was received or sent from that district.

Given the clear advantages of wire fraud, we should expect to continue to see this charge being used as the go-to tool for federal white collar prosecutors pursuing criminal cases involving cryptocurrency and other digital assets. (Contact: Leo Tsao)

- SEC tells public companies to disclose crypto exposure: So now what?

In response to the highly-publicized collapse of several crypto trading platforms, the SEC’s Division of Corporation Finance (CorpFin) advised public companies on December 8 that they may need to disclose to investors their exposure and risk to distressed crypto assets and the crypto market generally. The SEC posted the informal guidance on its website a day after Chairman Gary Gensler gave an interview on Yahoo Finance where he defended the agency against criticism that it failed to take steps to prevent the recent spate of crypto bankruptcies and failed to protect investors. It is the first time CorpFin has provided specific guidance to public companies on disclosure requirements related to crypto.

CorpFin said it “believes that companies should evaluate their disclosures with a view towards providing investors with specific, tailored disclosure about market events and conditions, the company’s situation in relation to those events and conditions, and the potential impact on investors.” “Companies with ongoing reporting obligations should consider whether their existing disclosures should be updated,” it added.

The post states that “[i]n meeting their disclosure obligations, companies should consider the need to address crypto asset market developments in their filings generally, including in their business descriptions, risk factors, and management’s discussion and analysis.” As is the case with all SEC filings, such disclosures are triggered if required by rule or if they are material and “may be necessary to make the required statements, in light of the circumstances under which they are made, not misleading.”

The post also contains a sample comment letter that contains a non-exhaustive list of the issues that companies should consider disclosing, including:

- “material impacts of crypto asset market developments, which may include a company’s exposure to counterparties and other market participants;

- risks related to a company’s liquidity and ability to obtain financing; and

- risks related to legal proceedings, investigations, or regulatory impacts in the crypto asset markets.”

While the post appears to be targeted at public companies that hold crypto assets or are involved in the crypto markets and depends on the company’s “particular facts and circumstances,” it may apply to companies that have indirect exposure to crypto risk through counterparties and other market participants and events: “Companies may have disclosure obligations under the federal securities laws related to the direct or indirect impact that these events and collateral events have had or may have on their business.”

Although the guidance does not create any new disclosure or reporting obligations, public companies should take note and assess their exposure, if any, to potentially distressed cryptocurrency assets, counterparties and events because they may receive one of the sample comment letters from CorpFin embedded in the web post during their next SEC filing review process. (Contact: Ken Herzinger)

- How to Serve a DAO: An Ooki DAO Update

Our October edition of Top PHive discussed the CFTC’s actions involving Ooki DAO, which included a settlement with bZeroX and its two founders concerning CEA violations for illegal off-exchange retail transactions involving “leveraged positions whose value was determined by the price difference between two digital assets.” The Commission’s settlement order characterized the DAO as “an unincorporated association,” defined as “a voluntary group of persons, without charter, formed by mutual consent for the purpose of promoting a common objective.”

In parallel to the settlement, a related civil complaint was filed in the Northern District of California against bZeroX’s successor entity, Ooki DAO. This raised the tricky question of how to properly serve notice on a DAO. The CFTC sought permission to serve the complaint on Ooki DAO by using the trading protocol’s help chat box and online discussion forum. In its motion, the Commission alleged that the Ooki DAO was intentionally structured to render its activities “enforcement-proof” by “erect[ing] significant obstacles to traditional service of process.”

After the Judge in the case granted the CFTC’s first motion for alternative service of process in September, several groups moved to file amicus briefs in support of Ooki DAO, and in defense of DeFi more generally, challenging the method of service. The amicus briefs -- which the Judge construed as Motions for Reconsideration of his previous order granting alternative service -- argued that the Ooki DAO cannot be sued, and therefore cannot be served, because it is a technology or smart contract, and not a legal entity. However, in a December order concluding that service had been achieved, the court rejected these arguments and held that “[a]t this point in the proceeding, fairness requires recognizing the DAO as a legal entity because as alleged in the complaint, the protocol itself is unregistered in violation of federal law, and someone must be responsible.”

The order specifically pointed to the CFTC’s allegations that the protocol was developed and controlled by bZeroX and its founders through their Administrator Keys. In this context, control of the Protocol “include[ed] … making changes to the software, deciding to distribute funds to defrauded users, and eventually choosing to transition control of the software.” It also included bZeroX transitioning the Administrator Keys to Ooki DAO’s token holders. But, the order explains, because the means of control were unchanged from the predecessor entity to the successor, the CFTC is able to serve Ooki DAO “as an entity for its use of Keys to control and govern the Protocol.” The Ooki DAO’s response to the complaint was due on January 10; when no response was filed, the CFTC asked the court to enter a default judgment against the Ooki DAO.

There appears to be a developing trend. While the holding was focused on the narrow issue of the sufficiency of service, and did not conclusively decide whether Ooki DAO is a legal entity, the court’s opinion (even if it is merely dicta) has already been cited as supplemental authority in two separate proposed class action cases against DAOs. And, in a criminal complaint charging Avraham Eisenberg with commodities fraud and manipulation, the DOJ identifies another DAO as the victim of the fraud, and describes it as “an entity structure in which there is no central decision-making authority, and such authority is instead distributed across token holders, who cast votes to make decisions.” In other words, it is alleged to be an unincorporated association under federal law, similar to the Ooki DAO.

The CFTC subsequently filed an independent suit against Avraham Eisenberg, repeating the allegations made in the criminal complaint about the status of the DAO (MNGO, “the native token of Mango Markets,” functioned as the governance token of the Mango DAO, “meaning that MNGO token holders may vote those tokens to govern (e.g., to modify, operate, market and take other actions with respect to) Mango Markets).” Interestingly, the CFTC described Eisenberg’s alleged scheme as “oracle manipulation.” “An oracle is a program that pulls data from an off-blockchain source and brings it onto the blockchain so that it may be used by smart contracts.” The CFTC alleges that Eisenberg used the oracle program to manipulate prices on Mango Markets in violation of the CEA. (Contacts: Michael Spafford and Ben Seelig)

- Federal Regulators Flash Red Lights at Banks’ Involvement in Crypto

“The events of the past year have been marked by significant volatility and the exposure of vulnerabilities in the crypto-asset sector.”

With this sentiment, federal banking regulators, including the Federal Reserve, FDIC, and OCC, issued a joint statement on January 3rd highlighting a laundry list of risks they believe are related to the crypto-asset sector and that should be front of mind for banks. Non-banks that partner or provide services to banks should also be focused on this guidance.

The risks identified by regulators include a wide range of concerns, most of which have been the subject of prior and ongoing commentary and guidance by the agencies. For example, key risks include:

- the risk of fraud and scams

- legal uncertainties related to custody practices, redemptions, and ownership rights;

- inaccurate or misleading representations and disclosures and other practices that may be unfair, deceptive, or abusive

- volatility in crypto-assets

- susceptibility of stablecoins to run risk

- contagion risk within the crypto-asset sector resulting from interconnections among certain crypto-asset participants

- lack of maturity in risk management and governance practices

- heightened risk related to decentralized networks, and

- cyber-attack vulnerabilities.

With this guidance, and in light of crypto-asset events of 2022, regulators are laser focused on ensuring the “risks related to the crypto-asset sector that cannot be mitigated or controlled do not migrate to the banking system.” To that end—although taking pains to say that no particular class of banking customers permitted by law should be foreclosed—the joint statement says that the agencies believe 1) holding crypto-assets on a permissionless or decentralized network, and 2) business models concentrated in crypto-asset-related activities or exposure are inconsistent with safe and sound banking practices.

Although this is a stronger position against involvement with crypto-assets than we’ve seen previously from this group of regulators, the guidance primarily emphasizes regulatory approval requirements that were previously issued applicable to entry into crypto-asset-related activities. For those already engaged with crypto, and those thinking about new business in that arena, we suggest focusing on the “key risk” most easily within a financial institution’s control, and where there has been perhaps the biggest regulatory disappointment. Namely, ensuring a maturity and robustness of risk management and governance practices. (Contact: Laurel Loomis Rimon)

- FinCEN will Grant Limited Access to Beneficial Ownership Information for Financial Institutions

On December 15, FinCEN issued a proposed rule to implement the access authorizations and restrictions for beneficial ownership information that many companies will be required to begin reporting to FinCEN on January 1, 2024. If you are a financial institution looking for the “it” gift of the holiday season, the proposed rule feels like a pair of socks. While FinCEN could have granted institutions query access to the beneficial ownership database to relieve some of the burden they separately carry related to their obligations under the Customer Due Diligence rule, the proposed rule limits financial institutions’ access to only information for those customers from whom they have obtained specific consent. Additionally, the information a financial institution can access through the database is of limited utility because FinCEN has not committed to verifying the beneficial ownership information that it receives and is not granting a safe harbor to financial institutions that rely on the beneficial ownership database. Federal regulatory agencies also face limits, as the proposed rule only allows federal regulatory agencies access to the data provided to the institutions by FinCEN to fulfill the regulators’ supervisory authority.

On the other hand, federal agencies engaged in national security, intelligence, or law enforcement activities will be able to request access to all beneficial ownership information maintained in FinCEN’s database. Considering that the Department of Justice actively investigates financial institutions for willful violations of the Bank Secrecy Act (“BSA”), the more expansive access granted to law enforcement agencies as compared to the access allowed to financial institutions and their regulators reflects a relative disadvantage to financial institutions in fulfilling BSA expectations.

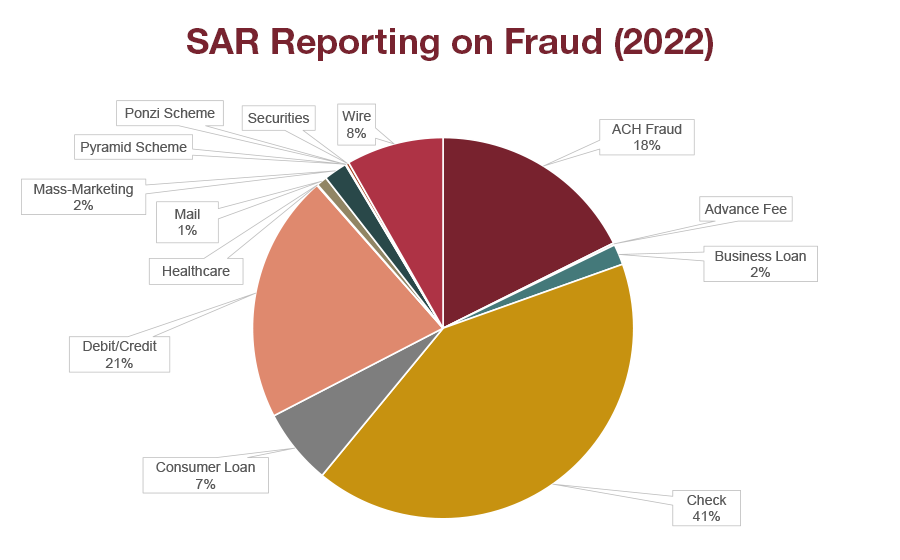

Financial institutions should consider commenting on the proposed rule, including requesting broader access to allow institutions to fulfill their regulatory obligations under FinCEN’s customer due diligence rule. Given the access granted to law enforcement agencies, providing financial institutions query access to the beneficial ownership data would not only alleviate compliance burden, but enhance the reporting that institutions can provide to FinCEN through suspicious activity reports. To address privacy concerns about financial institutions having broad query access, these queries could be limited to allowing financial institutions to verify the information they received from their customer. Financial institutions have until February 14th to submit comments on the proposed rule. (Contact: Braddock Stevenson)

To continue to receive the latest Top PHive Crypto Enforcement Notes, please click here to subscribe.

Contributors