Client Alerts

Top PHive Crypto Enforcement Notes: December Edition

December 08, 2022

By

Laurel Loomis Rimon,

Leo Tsao,Braddock J. Stevensonand Ben Seelig

Well, it was another quiet month in crypto . . . Not. We are still watching the tsunami play out in real time, as governments and the crypto market react to another seismic shift in the crypto landscape. While events of the last month raise numerous important questions, our focus here is on the issues affecting financial services companies, particularly Fintechs and crypto-involved companies, that continue to build and develop compliance-focused platforms. The path ahead remains open, but, more than ever, it’s critical to stay ahead of the enforcement issues that are on the horizon.

Well, it was another quiet month in crypto . . . Not. We are still watching the tsunami play out in real time, as governments and the crypto market react to another seismic shift in the crypto landscape. While events of the last month raise numerous important questions, our focus here is on the issues affecting financial services companies, particularly Fintechs and crypto-involved companies, that continue to build and develop compliance-focused platforms. The path ahead remains open, but, more than ever, it’s critical to stay ahead of the enforcement issues that are on the horizon.

- The CFPB’s Deep Dive on Crypto Consumer Complaints

- DOJ’s November Crypto Enforcement Hits

- Tornado Cash Part III – The Saga Continues

- The OCC and SEC Remain Vigilant Against Individuals

- What Happens When FinCEN Assesses a Penalty And the Subject Doesn’t Pay?

|

|||

- The CFPB’s Deep Dive on Crypto Consumer Complaints

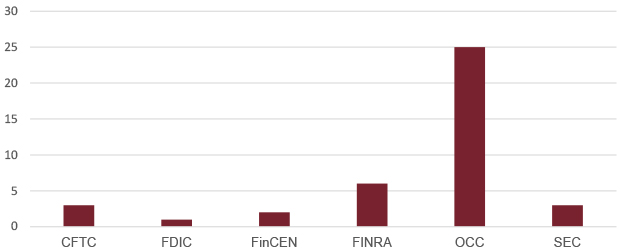

Individual Penalties by Regulatory Agency

(2018-Present)

On November 10th, the CFPB issued a 45-page “Complaint Bulletin” describing and analyzing crypto-asset-related complaints submitted by individual consumers through the Bureau’s complaint portal. Although the CFPB itself has yet to issue a crypto-specific rule or bring an enforcement action involving digital assets, it plays a key role in collecting consumer complaints and providing thought leadership to the federal and state regulators who may be closer to taking action.

The CFPB’s report stated that over 8,300 complaints had been submitted to the Bureau since 2018, with most having been received in the last two years. Other agencies have reported their own increases in crypto-related complaints, with the SEC reporting over 23,000 tips, complaints, and referrals since fiscal year 2019 involving crypto-asset activities, and the FTC reporting that it has received over 46,000 claims of loss to crypto scams since early 2021.

Relatively speaking, the CFPB’s 8,300 complaints do not stand out as a particularly large number over four years, but there are a few things to keep in mind. First, crypto has not thus far been a broad consumer-facing financial product or service of the type involving the CFPB. Additionally, the 8,300 number does not include several categories of potential complaints, including those that were referred to another agency for investigation and follow-up, those where the consumer didn’t expressly opt in to disclosure, complaints where the company had not yet had 15 days to respond, and complaints where it wasn’t possible to properly anonymize the information for publication. These 8,300 complaints, then, are likely the tip of the iceberg.

The CFPB’s bulletin goes into substantial detail about the type of business conduct, scams, and service problems that comprise the universe of complaints, including numerous extracts from consumer submissions that demonstrate the frustration and loss many consumers have encountered:

My family and I have 4 accounts with [crypto-asset platform]. All of a sudden, we are still able to log into our accounts, but the accounts are "restricted" and it is NOT possible to make any transactions or close the account. There is NO one at the company to talk to...only website inquiries.

I sent the [crypto-asset] not knowing it was a scam. I would like my money back. I saved it for years and was investing it. I didn’t know this was a scam.

Fraud and scams constituted about 40% of the complaints identified by the CFPB, while the remaining 60% were comprised of transaction and service problems, including funds availability, problems with terms and disclosures, and other issues.

The CFPB’s Complaint Bulletin is primarily an effort to demonstrate federal leadership in consumer protection in the crypto asset space, but does provide a few takeaways that are consistent with the approach of other regulators like the FTC, NYDFS, and state Attorneys General, and apply to non-crypto Fintech companies as well. First, financial services companies cannot get away with skeletal customer service support structures. Consumers must have a meaningful way to raise issues and receive a timely response. Second, consumer disclosures—particularly when it comes to crypto assets—require superior communication and marketing skills that most companies don’t currently have. There needs to be investment in these skills and resources. Finally, regulators are especially focused on how “special populations”—seniors and service members, for example—are affected. Enforcement action is likely to focus first on protecting these groups. (Contact: Laurel Loomis Rimon)

- DOJ’s November Crypto Enforcement Hits

The DOJ continued its cryptocurrency enforcement spree last month, with two large-dollar actions involving blatant fraud and money laundering out of the Southern District of New York and Western District of Washington. From historical fraud against a notorious darknet platform itself, to a crypto mining Ponzi scheme, the DOJ is actively focused on crypto-related seizures and convictions.

First, on November 7th, the DOJ announced a “historic $3.36 billion cryptocurrency seizure and conviction related to the Silk Road Dark Web Fraud.” The number is based on the value of a Bitcoin seizure that actually took place a little more than a year ago, in November 2021, so it’s not quite as historic a number at today’s prices. Nonetheless, it’s an attention-grabbing headline from the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, who secured a guilty plea from defendant James Zhong for committing wire fraud against the Silk Road darknet marketplace itself. Zhong was charged with having exploited a technical vulnerability in the Silk Road platform to steal and then launder at least 50,000 Bitcoin that were known to be criminal proceeds.

The fraud committed by Zhong actually took place in September of 2012, and involved the defendant creating accounts on Silk Road with minimal identity information, quickly depositing a sum of Bitcoin, then using a technical vulnerability to immediately execute multiple withdrawals in rapid succession of a substantially greater amount of 50,000 Bitcoin. Almost five years later, Zhong was the beneficiary of a hard fork coin split between Bitcoin and Bitcoin Cash, which resulted in a duplicative amount of BCH, which he later exchanged through a foreign cryptocurrency exchange for more Bitcoin.

In a separate action on November 21, the DOJ unsealed an indictment in the Western District of Washington against two Estonian citizens who were arrested and charged with operating a $575 million blatant fraud scheme, offering contracts for rentals in the HashFlare cryptocurrency mining operation, which did not in fact exist. The defendants were also charged with offering investments in Polybius, which they promoted as a developing bank that would specialize in cryptocurrency but was never actually formed or returned any dividends. In truth, both projects operated as large Ponzi schemes, drawing in customers from around the world.

According to the indictment, much of the over $500 million the defendants collected flowed to accounts at financial institutions and virtual asset service providers in various countries, including the United States, in the names of shell companies and other individuals working with them. The defendants provided financial institutions with fraudulent documentation for their shell companies and false explanations of the nature and source of funds being transferred. They also controlled and used numerous unhosted wallets and their own virtual asset service. Some of the defendants’ efforts at obfuscation involved a “peel chain” technique involving a series of transactions in which a smaller amount of Bitcoin is transferred to a new address each time.

A blockchain based financial institution focused on compliance may wonder: What can I learn from these prosecutions? One obvious point related to the Zhong case is, the government (at least in this instance) believes that “an important and common function served by decentralized Bitcoin mixers is to obfuscate one’s control over and the source of Bitcoin.” Additionally, as is clear from the fact that that case spanned over 10 years, criminal proceeds can have a long tail, and the government is especially interested in tracing assets that are a part of investigations—like the Silk Road Dark Web series of cases—in which it has already made a significant investment of time and resources.

Significantly, in both cases, criminals made use of non-charged virtual asset exchanges and service providers. It is always possible that the government may have investigative information that connects apparently legitimate activity on a platform to an illicit actor. This connection may not be obvious to the platform itself, which may be receiving false or fraudulent information from the subjects. The best defense and method of keeping scrutiny away from a compliance-focused platform is to be able to demonstrate the collection and monitoring of good-quality customer data combined with robust transaction monitoring and suspicious activity reporting. (Contact: Laurel Loomis Rimon)

- Tornado Cash Part III – The Saga Continues

Four months (to the day) after OFAC first put the crypto blending or mixing platform Tornado Cash on the SDN list, the agency announced that it was delisting and simultaneously re-designating the open-source protocol for its support of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’s (“DPRK”) nuclear weapons activities. The initial designation and the subsequent clarifications, criticism, and celebrity dusting were covered in previous editions of Top PHive, but a quick recap might be in order for those who’ve lost the plot:

- On August 8, OFAC designated Tornado Cash and around 40 wallet addresses associated with the service as sanctioned “entities,” marking the first time that Treasury chose to list smart contracts or open-source software on the SDN.

- Following outcry and confusion from many in the crypto community, Treasury published guidance on September 13 on the availability of specific licenses for U.S. persons wishing to complete transactions with Tornado Cash.

- In September and October, two separate lawsuits were filed in Texas and Florida federal district courts on behalf of Tornado Cash users and a nonprofit advocacy group claiming that Treasury overstepped its regulatory authority and violated plaintiffs’ constitutional rights.

Then, on November 8, Treasury re-designated the Tornado Cash protocol for allegedly helping launder the proceeds of several cyber heists carried out by the Lazarus Group, funds which were later used to fund DPRK’s WMD program. Specifically, the new designation alleges that Tornado Cash “materially assisted, sponsored, or provided financial, material, or technological support for, or goods or services to or in support of the Government of North Korea” and “facilitate[ed] the laundering of proceeds of cybercrimes,” including attacks conducted by the DPRK-affiliated Lazarus Group.

Treasury’s re-designation lists the originally sanctioned wallet addresses as well as an additional 53 addresses affiliated with Tornado Cash. It further sanctioned two individual DPRK authorities for taking part in DPRK’s ballistic missile and weapons program, and issued new (and updated) FAQs on the impact of the re-designation.

The fact that Treasury’s most recent announcement explicitly links Tornado Cash to the funding of North Korea’s nuclear program is not much of a surprise, since the original designation contained several references to the Lazarus Group’s connection with the DPRK regime. Rather, what is most intriguing is the announcement’s characterization of the protocol’s structure, specifically how Tornado Cash used smart contracts to “implement its governance structure, provide mixing services, offer financial incentives for users, increase its user base, and facilitate the financial gain of its users and developers.” The re-designation still does not, however, name any of the individuals who participated in the Tornado Cash DAO, or those who were responsible for developing or maintaining the service, although some of the protocol’s developers already face charges, or the threat of criminal action, in the Netherlands.

Whether this new designation will survive the ongoing legal challenges to Treasury’s authority to list open-source code as a sanctioned “person” under E.O. 13694 remains to be seen. Just a few days after Treasury’s announcement, plaintiffs in the lawsuit pending in Western District of Texas filed an amended complaint, alleging that Treasury’s re-designation “on the eve of the [government’s] deadline to respond” to their original complaint still lacks the necessary statutory authority. (Contacts: Ben Seelig, Braddock Stevenson and Laurel Loomis Rimon)

- The OCC and SEC Remain Vigilant Against Individuals

Under consistent pressure from Congress and the public to hold individuals accountable for corporate misdeeds, the OCC and SEC have continued a steadfast pattern of civil monetary penalties against individuals for their role in the failings of banks and broker/dealers to comply with regulatory requirements. Unlike the DOJ, which has to demonstrate that an individual’s willful actions were the cause for a corporation’s misdeeds, federal regulators have procedural authorities that subject individuals to penalties for failing to correct a financial institution’s compliance deficiencies.

In particular, Title 12 grants the OCC and other banking agencies the authority to impose penalties and issue prohibitions against individuals determined to be an “institution affiliated party” (“IAP”). IAPs include directors, officers, employees, controlling stockholders, and, in certain circumstances, any independent contractor (including any attorney, appraiser, or accountant) who knowingly or recklessly participates in a violation of law, breach of fiduciary duty, or unsafe and unsound practice that caused a more than minimal financial loss to the institution.

Correspondingly, under Sections 15(b)(4) and 15(b)(6) of the Securities Exchange Act, the SEC has authority to impose penalties against individuals within a broker-dealer who have supervisory obligations and fail to reasonably supervise personnel with a view of preventing violations of the federal securities laws, the Commodity Exchange Act, and the rules and regulations implementing such laws. Included in this authority, the SEC has explicitly stated that it is unreasonable for a person in a supervisory position to ignore wrongdoing or red flags that suggest irregularity.

Since 2018, banking and securities regulators have brought 35 actions against individuals and assessed over $800,000 in penalties for AML-related failures alone. The OCC is the most active in assessing these penalties, accounting for 25 of the 35 assessed penalties. In 2018, the OCC assessed its highest penalty of $175,000 against a CEO for participating in the bank’s BSA violations that included, per the bank’s agreement with FinCEN, retaliating against the bank’s AML officer.

While these actions are typically nominal and rarely make headline news, they are a strong reminder to institutional managers and supervisors of the personnel risks they take when their institution violates the BSA. In sum, compliance officers and supervisory personnel overseeing compliance or regulated activity should be mindful of the type of actions that can result in individual liability for a company’s noncompliance. (Contact: Braddock Stevenson)

- What Happens When FinCEN Assesses a Penalty And the Subject Doesn’t Pay?

On October 19, the DOJ, on behalf of FinCEN, filed a complaint in the District Court for D.C. against Larry Harmon to collect on a civil money penalty of $60 million that FinCEN assessed against him in October 2020 for failing to register as a money services business and conduct proper anti-money laundering compliance. Although FinCEN can assess a civil money penalty for willful violations of the BSA, it relies on DOJ to bring civil actions to enforce those penalties. But what standard of review will the court use in adjudicating the government’s claims? Will deference be given to the factual and legal findings FinCEN has made during the administrative penalty assessment stage? Or, will district court proceedings be de novo, with an opportunity for discovery and fresh defenses?

OFAC, for instance, has been granted deference for its penalty determinations, meaning they would have to be found to be “arbitrary and capricious” before being overturned, on the basis of its administrative enforcement procedures and regulations where subjects are provided with formal due process. Specifically, OFAC issues a pre-penalty notice and provides an opportunity to respond to such notice prior to the assessment of a penalty. OFAC regulations provide detailed information on evidentiary standards, hearing requests, and use of Administrative Judges during the administrative stage.

FinCEN does not have the same administrative adjudication procedures in practice or regulation, although it has begun to try to establish them through, for instance, issuing a statement of Enforcement Factors in August 2020. The government has recognized in prior cases that the lack of administrative due process would result in a de novo review at the district court, positions it had to take in penalty actions by FinCEN and the IRS related to BSA violations.

More specifically, when FinCEN sought to enforce its assessment of a penalty against Thomas Haider for BSA violations in the District of Minnesota (transferred from SDNY) in 2016, Haider moved to dismiss the case in part based upon FinCEN’s lack of “regulations requiring it to afford meaningful pre-assessment process and review.” The government was in a position where it had to agree that “the civil action necessarily includes discovery and the right to a trial de novo on the fully developed record.”

While we are reading the tea leaves here, based on the language in the Harmon assessment and complaint, the Harmon complaint looks to us like an effort by FinCEN to obtain a judgment with a deferential standard of review. In particular, FinCEN discusses the fact that it provided a pre-assessment notice to Harmon and almost seven months of time for him to respond. It was not until after Harmon’s failure to respond that FinCEN assessed its penalty. Additionally, as compared to the Haider complaint, the DOJ complaint against Harmon is substantially lighter on specific facts and generally defers to FinCEN assessment to support the government’s complaint. Clarity on this issue will have to wait, however, as the matter is now stayed until after Harmon’s sentencing in his criminal case.

Nonetheless, this issue is of significant importance for entities that may be engaged with FinCEN in connection with investigations or potential settlements. The likely standard of review in any judicial action that would be necessary to enforce a penalty is a significant part of the calculation in negotiations with the government in much earlier stages. (Contact: Braddock Stevenson)

Bonus: OFAC’s Kraken Action Emphasizes Ongoing Monitoring

To cap off November, OFAC imposed a $362,158 fine against centralized U.S. cryptocurrency exchange Kraken for voluntarily self-disclosing apparent violations of the Iranian Transactions and Sanctions Regulations. In particular, OFAC determined that Kraken processed 826 transactions for $1.7 million that apparently violated the U.S. sanctions regime against Iran. In its enforcement release, OFAC stressed the importance of not only screening IP addresses at account opening but also continually throughout the lifespan of an account.

Under 31 C.F.R. § 560.204, U.S. persons are prohibited from provided services to Iran or the Government of Iran. Many firms rely on customer due diligence and geo-blocking to comply with these prohibitions. OFAC’s enforcement release emphasizes the need not just to have mechanisms in place to ensure an accountholder is not located in a sanctioned jurisdiction at the time of account opening, but to continually screen IP address information for subsequent transactions conducted by the accountholder. In this case, OFAC alleged that “[a]lthough Kraken maintained controls intended to prevent users from initially opening an account while in a jurisdiction subject to sanctions, at the time of the apparent violations, Kraken did not implement IP address blocking on transactional activity across its platform.”

In imposing its penalty, OFAC highlighted the mitigation provided against the maximum penalty of $272 million due to the self-disclosure of the violations, the fact that Kraken had systems in place to comply during account opening, and that it also implemented additional systems to geo-block IP addresses for subsequent transactions. This action is a reminder to financial institutions that the government expects policies and procedures will screen and geo-block throughout the lifespan of an account. Accounts that are clear at the time they are opened can become sanctioned over time through movement of accountholders and/or changing designations. (Contact: Braddock Stevenson)

To continue to receive the latest Top PHive Crypto Enforcement Notes, please click here to subscribe.

Contributors