Client Alerts

Recognition of Restructurings in Europe

June 02, 2021

By

David Ereira

and Anna Nolan

Prior to the end of the transition period (31 December 2020), U.K. restructuring tools enjoyed universal and automatic recognition throughout the European Union. However, the legal landscape is now tainted with uncertainty and the legal position regarding recognition is more complex. Recognition is important to ensure that a scheme of arrangement, a restructuring plan, or a company voluntary arrangement (“CVA”) is fully binding on parties and to minimise the risk of challenge.

Brexit has significantly affected cross-border recognition of restructuring processes in the European Union. Following 31 December 2020, the U.K. is no longer within the scope of the EU’s Recast Insolvency Regulation. This means that formal U.K. insolvency processes such as administrations, liquidations, and CVAs that opened after the end of the transition period are no longer automatically recognised in the EU under the EU’s Recast Insolvency Regulation (recognition of formal insolvency processes other than CVAs is outside the scope of this note). Similarly, for schemes of arrangement, and arguably also restructuring plans commenced after 31 December 2020, the EU Judgment Regulation does not apply. This note will focus on outbound and inbound recognition of schemes of arrangements, restructuring plans, CVAs, and similar restructuring tools in Europe.

English companies often use schemes and restructuring plans to compromise their English law governed debt. An English court will only sanction such schemes and plans for a foreign (non-English) company if there is a sufficient connection with the English jurisdiction and it is likely that the scheme or plan will achieve its purpose. Notably, English courts may refuse to sanction a scheme or plan if it will not be recognised in any of the relevant foreign jurisdictions where the debtor operates (Re Gategroup Guarantee Limited [2021] EWHC 304 (Ch), [172]).

CVAs are normally used to compromise unsecured claims arising under English law governed contracts.

Outbound recognition

The main methods allowing for recognition of an English scheme of arrangement, restructuring plan, or CVA in an EU member state (outbound recognition) are:

- Regulation (EC) No 593/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 June 2008 on the law applicable to contractual obligations (“Rome I”)

EU member states will still apply Rome I in respect of English law governed contracts so outbound recognition of schemes, restructuring plans, and CVAs compromising English law governed debt remains unaffected by Brexit. Similarly, the U.K. allows for inbound recognition of European equivalents to English schemes as a result of the retention of Rome I post-Brexit.

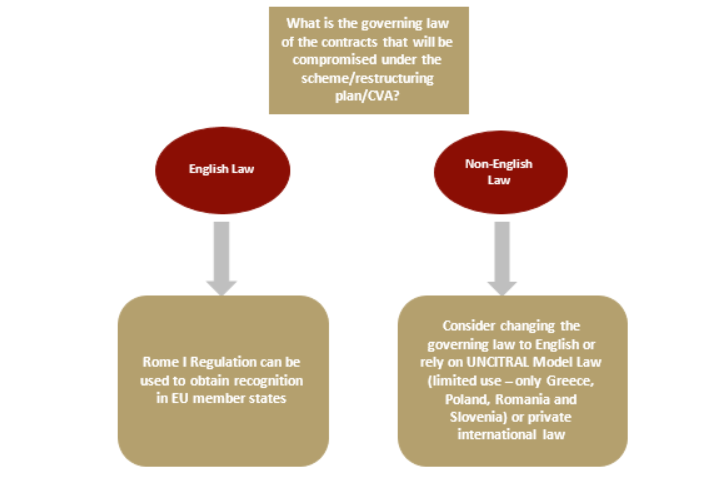

Rome I provides that contracting states should give effect to contracting parties’ choice of the law governing their contractual relations. Under Rome I, the law applicable to a contract shall govern the various ways of extinguishing the obligations under that contract. Accordingly, if the obligations to be extinguished or varied under a scheme, a restructuring plan, or a CVA are governed by English law, then recognition of a scheme, a restructuring plan, or a CVA across the EU can be obtained under Rome I. However, if the governing law of the underlying contract to be compromised is not English, Rome I cannot be relied upon in order to obtain recognition of English schemes, restructuring plans, and CVAs in an EU member state. The parties may want to consider changing the governing law of the debt to be compromised from non-English law to English law to rely on the Rome I Regulation and to establish a stronger nexus with the U.K.

- The 2005 Hague Convention on Choice of Court Agreements (“Hague Convention”)

The EU is a contracting party to the Hague Convention, meaning the convention applies to all EU member states. The U.K. is now also a contracting party in its own right following its accession with effect from the end of the Brexit transition period.

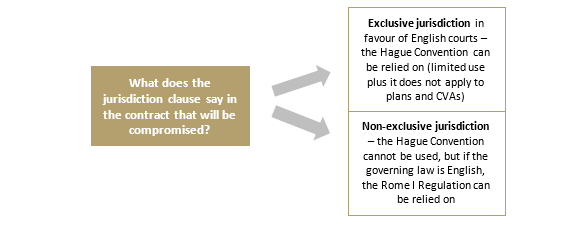

The Hague Convention provides a framework of rules relating to jurisdiction in civil and commercial matters, as well as the subsequent recognition and enforcement of judgments given by the courts of a contracting state. It can be relied upon to obtain recognition of schemes of arrangement in an EU member state provided that the law of the obligations being compromised or extinguished is subject to an exclusive jurisdiction clause in favour of English courts.

In order to rely on the Hague Convention, parties to new loan agreements and other contracts may want to consider including an exclusive jurisdiction clause given that the Hague Convention does not apply to one-way or asymmetric jurisdiction clauses, which are for the benefit of one party only (permit party A to sue party B in any competent jurisdiction, but restricts party B to bringing proceedings in only one jurisdiction). For example, obiter comments of the Court of Appeal in the recent case of Etihad Airways PJSC v Flother [2020] EWCA Civ 1707 suggested that the definition of an “exclusive jurisdiction clause” for the purposes of the Hague Convention would not include asymmetric jurisdiction clauses. Further, the Explanatory Note to the Hague Convention states that asymmetric jurisdiction clauses are not exclusive for the purposes of the Hague Convention and so are outside its scope. Currently, the majority of jurisdiction clauses in English law loan agreements are asymmetric, whereas a further potential limitation of the Hague Convention is that it is unclear from when it applies to the U.K. (1 October 2015 when the EU acceded or 1 January 2021 when the U.K. acceded in its own right).

The position is more complex in relation to restructuring plans and CVAs as they are likely to be held to constitute bankruptcy proceedings for the purposes of the Hague Convention and therefore will be excluded from its scope. That being said, if the Hague Convention does not apply, in order to obtain recognition of a plan or a CVA in EU states, the parties could still rely on Rome I if the relevant obligations or rights that are compromised under the plan are governed by English law. Accordingly, in practice, the Hague Convention will be relied on less often than Rome I, especially given the uncertainty surrounding contracts entered into prior to the U.K.’s accession.

- Lugano Convention

The U.K. has applied to join the Lugano Convention, but is still waiting for its application to be approved (with recent reports suggesting it is being opposed by the European Commission). The rules of the Lugano Convention would offer a substantially similar framework to the EU Judgments Regulation, allowing the U.K. and the EU to retain the benefits of the mutual recognition and enforcement of judgments.

If the U.K. accedes to the Lugano Convention, while schemes would benefit from uniform recognition in EU states, it would not be possible to rely on the Lugano Convention for recognition of restructuring plans (after the Gategroup judgment further described below) or CVAs (which are outside the scope of the Lugano Convention as insolvency processes).

The recent judgment of Mr Justice Zacaroli in Re Gategroup Guarantee Limited has a significant impact on recognition of restructuring plans under the Lugano Convention. It focuses on the restructuring plan requirement that the debtor must be facing “financial difficulties” (the same requirement does not apply to schemes). Zacaroli J held that, unlike schemes, restructuring plans are outside the scope of the recognition provisions under the Lugano Convention.

- UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross-Border Insolvency (the “Model Law”)

The Model Law provides a framework by which domestic courts may recognise foreign insolvency proceedings. Recognition of English schemes, restructuring plans, or CVAs may be possible in EU states that have enacted the Model Law, although the scope of recognition may depend on the laws of the applicable state.

However, certain jurisdictions may only provide recognition limited to local remedies and may not include a permanent stay of proceedings against the debtor in relation to the compromised debt. In addition, at the moment, there are only four EU countries that have adopted the Model Law (Greece, Poland, Romania, and Slovenia) and it remains to be seen if other EU countries will decide to adopt it. Another interesting point to consider is what happens if recognition is obtained in an EU state under the Model Law and how that would affect recognition in the other EU countries.

- Private international law

If none of the rules and regulations identified above can be relied on to obtain recognition, English schemes, restructuring plans, or CVAs may be recognised in an EU member state under its private international law either as a matter of recognition of foreign judgments (in which case, certain local conditions to recognition may need to be considered while drafting the scheme, restructuring plan, or CVA documentation) or application of non-English law (e.g., where a scheme compromises English law debt). Recognition of schemes, restructuring plans, or CVAs under private international law of EU member states would need to be reviewed on a case by case basis and will be particularly important if a scheme, a restructuring plan, or a CVA sought to affect a company with assets in a foreign country (where creditors may want to take action against the debtor in that country).

Flow-charts regarding outbound recognition

Recognition based on the governing law

Recognition based on the jurisdiction clauses

Inbound recognition

Debtors who use EU restructuring tools similar to an English scheme or restructuring plan will typically want to ensure that such process is recognised in the U.K. if there is a nexus with this jurisdiction (i.e., inbound recognition). Most notably, the U.K. may soon need to consider the recognition of German or Dutch schemes of arrangements.

The methods used to recognise EU restructuring processes will be the same as those stated above in the context of outbound recognition.

The U.K. has adopted the Model Law through the Cross-Border Insolvency Regulations 2006 (notably there is no requirement of reciprocity). This means that foreign representatives of relevant non-English proceedings in EU member states can have access to the English courts and seek recognition (recognition is not automatic).

By way of a reminder, if English law is chosen by the contracting parties, the rule, as set out in Antony Gibbs & Sons v La Societe Industrielle et Commerciale des Metaux 1890, is that an English law contract will not be discharged by a foreign insolvency process. Following the judgment in Re OJSC International Bank of Azerbaijan [2018] EWCA Civ 2802, the English court will not grant discretionary relief that has the effect of displacing, or circumventing, the common rule in Gibbs. The rule in Gibbs will likely prevent the EU member states trying to compromise an English law governed debt under their own scheme of arrangement or a similar process. If the EU restructuring process will not be recognised in the U.K., it may be necessary to run a parallel U.K. process to provide certainty for interested parties.

Conclusion

Recognition of U.K. restructuring tools in the EU is more uncertain following Brexit, but once stakeholders become more familiar with the new legal landscape, the process of obtaining recognition will become clearer. In the absence of automatic recognition, while preparing for cross-border restructurings or distressed situations it may be necessary to consider recognition rules in each country in which the U.K. based debtor operates. It may be necessary to have parallel processes in place in addition to a U.K. process in order to provide certainty of implementation. Moreover, legal practitioners working on restructurings with a U.K. nexus may need to be more creative. An interesting example of establishing nexus with the U.K. in order to implement a U.K. restructuring plan is Gategroup. The company’s restructuring plan utilised a “co-obligor” structure. This involved the incorporation of an English newco, which then executed a deed of indemnity and contribution (a deed poll) in favour of the senior lenders and the bondholders. Gategroup then proposed a restructuring plan seeking to compromise the claims of the senior lenders and the bondholders against the English newco under the deed poll and the creditors’ claims against the original obligors. The COMI of the bond issuer has been moved to England. However, if and how the Gategroup restructuring plan will be recognised in Switzerland, where the group has its headquarters, remains to be seen.